The dreaded “login button” has been put on websites since the advent of bulletin boards as a means to moderate forums. Later the login button served e-commerce and also publisher’s websites as a way to get to know the consumer a bit more for personalised advertising. The login button became an integral part of a website’s platform.

Facebook Connect, launched in 2008, changed the traditional login. With Facebook Connect, a consumer could login and share their personal details with a website in a single click. Consumer profiling became hot and in fact, access control was believed to be a necessity or at least a handy excuse to gather private details.

Today, the login button is increasingly confusing the consumer: how is privacy preserved?, what consents am I giving or are being implied? It is being hated more and more: “I do not need to prove my identity when I enter a festival, so why do I need to do this when I read an article? What is happening and how to resolve this?

From login to policy verification

Is the login button a core capability? Of course it is not. But policy enforcement (see our post here) can be. A ‘policy’ consists of the conditions that must be met before people, systems and services can do something. Policy enforcement needs policy verification that checks security and business rules such as:

- did the user pay for this type of function?

- does the user have a valid subscription?

- did the user already consumed the free passes?

- does the user have adequate certification?

- has the user been assigned the necessary role?

- is the user located in a whitelisted country?

- is the user a delegate of an authorised person?

- the user not blacklisted for commenting?

- does the user have a caring relationship with the owner?

- did the user already register for this event?

- did the user give their consent relative to this?

Policy enforcement is the capability to make sure that a user complies with the enterprise policy before they can do something. After reading our post “What is an enterprise capability?” it may become clear that policy enforcement can even become a core competency. Much like handling payments has been a core capability of B2C enterprises since long, even before e-commerce and even the Internet existed. Policy enforcement is the capability that enables monetisation of digital services. It protects against revenue leakage caused by free-riding, fraud and bad behaviour. Furthermore, it protects against reputational damage by securing the information that was provided by other people and organisations.

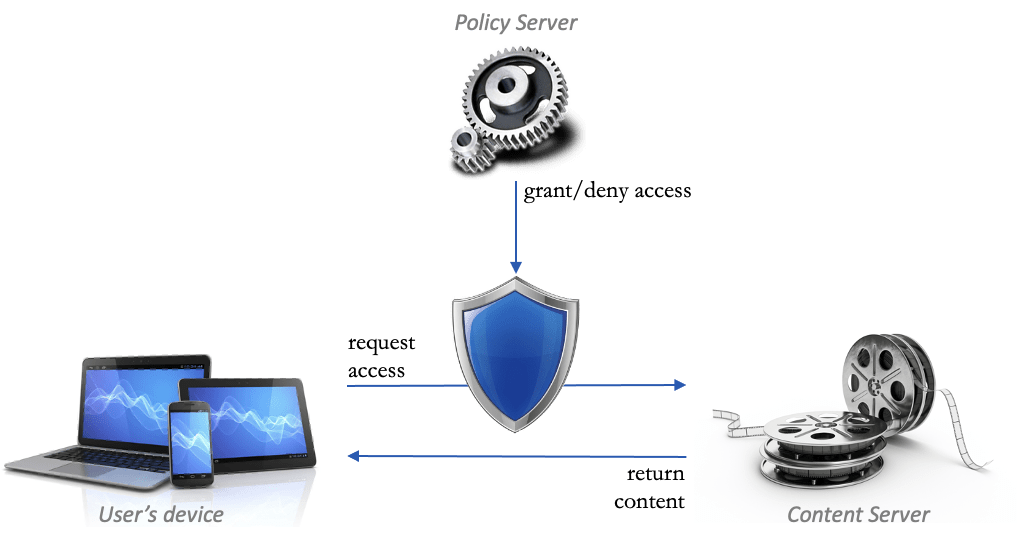

In fact, with the advent of token-based access control it has become clear that policy enforcement can be externalised by applications, websites and e-commerce services. Furthermore, recent microservice-based implementations made policy enforcement “headless” to further make abstraction of any user interface and any website/app/service. Policy enforcement can therefore be separated from its technological implementation and can become a core capability in its own right. Note that this architecture of taking policy enforcement out of applications/websites/apps is described by XACML.

The strategic goal of policy enforcement is to enable monetisation and protect against abuse. Its KPIs are thus “free-riding rate” and “abuse rate” which not only includes abuse by malicious adversaries but also abuse implied by consumers who share their credentials.

The finality of the policy enforcement capability is to govern access to digital content and functions. It authorises a user (or even a third party service used by that user) to access a piece of digital content or a function, at a particular moment in time and given a particular context.

The policy enforcement capability for an innovating digital business therefore…

- registers users in some way, preferably using headless self-service workflows. ‘Headless’ means that abstraction is made of its UI implementation and that workflows are offered as an API to apps, websites and services. The ‘self-service’ aspect means that manual support processes are minimised.

- maintains a record of digital users to enable them to be recognised. Even though this is often seen as “identity,” the actual, true identity of the user is strictly speaking not necessary for policy enforcement.

- responds to authorisation requests by evaluating the security and business policy. This response is a yes/no or a “yes but” and can be named or anonymous. Anonymous responses reduce the proliferation of private details.

- has some manual processes, such as a support desk, to handle incidents and to cover cases where a response cannot be given in an automated way: for example in case of conflicting information, in case manual approval is needed, or in case the consumer experiences difficulties.

- has a governance function to define, agree upon and maintain the security and business rules under strict change control.

The policy enforcement capability is a business enabler. It enables the monetisation of digital services while reducing revenue leakage and reputational damage. Authorising the use (and modification) of content and private data is driven by both a business and a security rules. Maintaining and evaluating those rules, and the governance and operational processes around them, are what constitutes the enterprise capability.

When evaluating those business and security rules, the policy enforcement capability may consult other enterprise capabilities to obtain further information about the consumer and their context, such as an identity store, a customer management system, and a community graph.

It may be clear that the information needed to answer these question may come from the capability managing subscriptions and payments, the capability managing personal details and profiling data of a consumer, and the capability managing communities and the relationships between consumers.

Implementing policy verification

Many websites/apps/services implement policy verification with a CIAM, a Customer Identity & Access Management platform. This is, however, not necessarily the best way to implement this core capability that is critical for digital business.

> Authorisation versus authentication

Many CIAM platforms focus on “authentication” rather than “authorisation.” Whereas authentication only proves that the consumer is present and the same who registered, authorisation is the decision whether a user can access something or not. The latter is what matters to achieve the enterprise goals. The former may be a precondition but is not sufficient (and may even not be necessary*).

Additionally, many CIAM platforms also offer/impose parts of the user interface. They are often not headless and require custom code on the client side. This has made the “login button” so dreaded.

New passwordless initiatives, such as FIDO2 and Sign in with Apple shake up old types of implementation: their fundamental premise is that a consumer is only authenticating locally to the device they trust, after which the device authenticates itself cryptographically to digital services without exchanging user passwords. The proposition of nextAuth (see our post here) goes one step further to also protect the consumer against man-in-the-middle attacks.

The authentication of a user, however, is only proving that the “request for authorisation” comes from a natural person. And while policy verification requires that requests come from an authenticated source, the source does not need to be a human being; it can equally be another service such as a third party microservice, cloud service or app.*

> Authorisation versus user profiling

CIAM platforms also collect a lot of private details. This is not because of authorisation considerations. It is simply because that’s how they have grown: their initial proposition was to enable Facebook Connect and/or to collect first party user data. This form of implementation is increasingly leading to privacy issues. The issue at hand is that they confuse user profiling with access control. User profiling should be based on actual consumer engagement (see our post on email use). In fact, “consumer understanding” should be seen as an enterprise capability in its own right. This capability serves a completely different goal, namely maximising customer lifetime value. This capability can then include for example sharing, gamification, sweepstakes, big data analysis for segmentation purposes and Machine Learning to better respond to consumer activity.

> AUTHORISATION versus access control

Some CIAM platforms rely on client-side enforcement of access control e.g. using Javascript. Some IAM platforms are implemented as an IAM-specific proxy service or API gateway: they act as a front door to the web services to conduct access control. Alternatively, token-based access control relies on an access token obtained from a policy decision point and passed on to web services. The access token is then used to grant access by the web service itself or by a generic, non IAM-specific API gateway.

Authorisation, i.e. policy verification, is the function to take policy decisions. It makes abstraction of how the decision is actually enforced. It is fundamentally a strongly governed request & response capability that provides a response using the context of the user and the agreed upon security and business rules. The digital business can then use this binary response to grant access or not, without custom logic and without worrying about profiles, profiles or payments. See our post on Policy Enforcement.

Concluding: considering policy enforcement as a core capability opens the way to innovative propositions and creates opportunities to rethink monetisation of your digital business and outperform other players. When implementing policy enforcement using off-the-shelf technologies, know that authentication, secure proxies and identity stores are ‘features’ that are optional and do not fully meet the goals of the enterprise capability.

Notes

*Authentication of the consumer may not be be necessary, for example, when the consumer is working through a third party app. This third part app may have been authorised to access your digital services on behalf of a consumer. The third party app may have authenticated the consumer but is not necessarily passing this on or is passing it on using some sort of authentication token (e.g. SAML, OpenID Connect, see also our post on Does OAuth 2.0 provide authentication?).

What type of use cases are we talking about? Well, imagine a publisher who not only counts on their own app and website, but also routes their content to apps of third parties, e.g. a social network, an event organiser, a football club or a news broker. The publisher can still monetise its content, can still attribute preferences to an anonymous consumer profile, but does not need to authenticate the consumer.

References

XACML 3.0, a standard framework for externalised authorisation

OAuth 2.1, a standard protocol for token-based authorisation

OpenID Connect 1.0, a standard protocol for token-based identification and authentication

SAML V2, a standard protocol for federated authentication and authorisation

FIDO2, a standard protocol for passwordless authentication

nextAuth, a commercial system implementing passwordless, mutual authentication